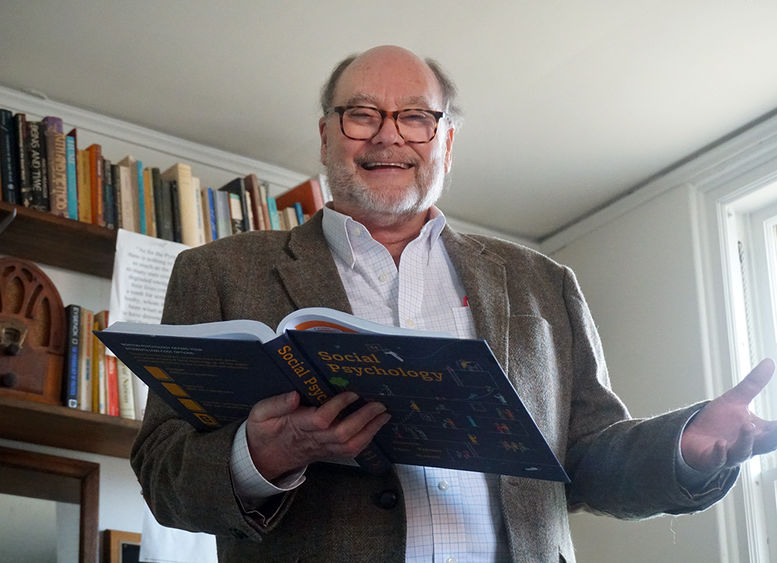

Penn State Hazleton Professor of Psychology Peter Crabb.

HAZLETON, Pa. — Peter Crabb is a social psychologist at Penn State Hazleton who does research and teaches classes on the topics that most people don’t want to talk about. Environmental issues like global warming, overpopulation, resource depletion, littering. Homicidal feelings in “normal” people. Aggressive behaviors related to COVID-19. The harmful impacts of technology.

Crabb has been a Penn State faculty member for more than 30 years — he taught at Penn State Abington for 16 years and transferred to Hazleton 15 years ago. A professor of psychology at Hazleton, Crabb has developed several upper-level courses for psychology majors that connect the real world with internal psychological processes.

His work centers on “how the actual cultural and social environments that people live in affect them, and how they in turn affect those environments,” Crabb said.

My teaching and research are aimed at helping young people get a grip on the various serious challenges facing our global society now, and trying to get them engaged in helping to make things better.—Peter Crabb , professor of psychology, Penn State Hazleton

“My teaching and research are aimed at helping young people get a grip on the various serious challenges facing our global society now, and trying to get them engaged in helping to make things better,” Crabb said. “Psychology students are naturally inclined to want to make the world a better place. So I’m trying to help them focus on specific issues, like sustainability, child abuse, technology and aggression.”

Student-involved research

Two of Crabb’s research projects involved Penn State students. One, on sustainability, involved Penn State Hazleton students in gathering and cataloging litter from three sites along public roads within a 30-mile radius of the Hazleton campus. Another, about the prevalence of homicidal thoughts among “normal” people, involved a survey of Penn State Abington students.

In his paper on sustainability (“Some Things Are Just Made To Be Littered”), Crabb reported that nearly 85% of the litter collected consisted of one-use items: cigarette butts, candy wrappers, and food and beverage packaging. While individuals actually do the littering, Crabb said that manufacturers and/or sellers of the one-use items bear a share of the responsibility for roadside waste.

“The argument in the paper is, because we’re finding very specific kinds of litter, and we’re not finding other objects along the sides of the roads, [the littering] has to be an interaction between the design of these products and the ‘affordances’ of the product, and the user,” Crabb said. “So, you put a user together with a Styrofoam cup and you get the Styrofoam cup on the side of the road.”

“Affordance” refers to the quality or property of an object that defines or clarifies how it’s going to be used. If retailers encouraged the use of reusable coffee cups instead of disposable ones, or if cigarette manufacturers used biodegradable cigarette filters, Crabb suggested in the paper, the need for expensive litter abatement programs would be reduced.

In his paper on the “material culture of homicidal fantasies,” Crabb reported that nearly half of the students responding to the survey indicated they could recall a recent homicidal fantasy. Nowadays, Crabb notes, homicidal thoughts confer no advantages on us.

But Crabb, whose undergraduate degree is in anthropology and who has a background in evolutionary science, noted in his paper that homicidal thoughts may have benefited our hominid ancestors. Eliminating competitors for food, water and shelter — as depicted in the early scene among the Australopithecine man-apes in “2001: A Space Odyssey,” which Crabb has screened for his students — would increase their chances for survival.

Crabb opened the paper with a bit of “journalistic pizzazz” — referencing a scene from “Strangers on a Train,” the 1951 Alfred Hitchcock movie, where a party guest vividly imagines how she might murder her husband. The scene illustrates how “homicidal fantasies may be a relatively normal phenomenon, with roots in the evolutionary history of the species,” Crabb wrote. (Normal, in this context, refers to something that happens more than it would by chance, or to thoughts or fantasies that are found in most human beings.)

“My argument is that we are descended from the most aggressive, murderous ancient humans,” Crabb said. “The nice peaceful folks of 100,000 years ago, they died off, and we didn’t get their genes. We got the genes of our aggressive, murderous ancestors, and so it shouldn’t surprise us, that under certain conditions, humans can be vicious, destructive creatures.”

Aggression during COVID-19

In a recent study on deliberate malicious attempts to spread the COVID-19 virus, Crabb found that reports of pathogen-spreading behavior increased fourfold during the early months of the pandemic. A typical perpetrator was an adult male who spat at other people and often claimed to be infected with the virus. In the paper, Crabb said the causes or motives for this behavior are unclear.

But he speculates that the behavior may have been sparked by stress. “Let’s start with the probability that most people are capable of being aggressive,” Crabb said.

“During the pandemic, the stress on people was huge. We couldn't do the things we normally did. We were living in fear of getting infected ourselves, or our families getting infected, and [the pandemic] disrupted our work lives. Psychologists have known at least since the 1930s, that when you have a lot of stress on individuals, they may well act out aggressively.”

In the future, Crabb hopes to research historical records and determine whether people acted out aggressively during earlier pandemics, such as the Black Death in the 1300s or the 2014-16 Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa.

Psychology, technology and sustainability

Crabb’s said his class on the psychology of technology helps students understand the technological world.

“They are the main adopters of new technologies, and I think it’s important for them to understand what they’re getting into when they adopt new technologies,” Crabb said.

For instance, every day students are using social media platforms like Instagram, Twitter and Facebook — but they may not realize that things they post to social media can be seen by potential future employers and could work against them.

In another class, on psychology and a sustainable world, Crabb tries to sensitize students to how their behavior impacts the Earth.

“Obviously, global warming, overpopulation and resource depletion are all issues that are happening right in front of our eyes,” Crabb said. “I think students need to be armed with some basic understanding of what’s happening to the planet, and why people’s thoughts and behaviors are making [detrimental environmental impacts] happen.”

Similarly, Crabb believes that the global economic system is in trouble and that huge shock waves are coming soon.

“I think we’ve reached the limits of growth, and we’re going to see some of that growth fall apart,” Crabb said. “Resources are finite. The planet is finite.”

It’s nice to live in a “consumer dream” where we can buy anything we want online, anytime we want, Crabb said. It seems like a wonderful way of life. And yet, unrestrained consumerism is harming the planet, is not sustainable, and can’t go on forever, Crabb tells his students. “My job is to teach young people, and that’s what I try to do,” he said.