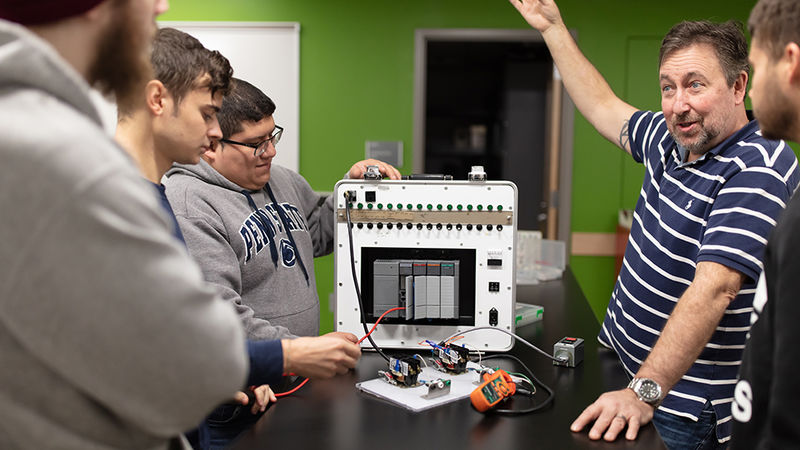

Ken Dudeck has helped make U.S. military ships and aircraft nearly invisible to enemy radar — but he’s been highly visible to his students

Ken Dudeck has worked on several top-secret Navy projects which helped make torpedoes quiet and U.S. military ships and aircraft nearly invisible to enemy radar — protecting the lives of American pilots and sailors in harm’s way. But Dudeck always knew he wanted to teach.